"Planning to write is not writing. Outlining--researching--talking to people about what you’re doing, none of that is writing. Writing is writing."

(E. L. Doctorow)

Monday, February 7, 2011

Tuesday, January 18, 2011

Plant that knife

Once upon a time, I was writing stories. I was trying to make them memorable. Things were exploding. People were dying. Knives were used. Guns were fired. Laser thingies were disintegrating aliens. Blood was splashed against stainless steel walls. Tears were never far.

But alas, no matter how many amazing tools and situations I was using – nothing felt truly dramatic. Every explosion, every knife planted in poor schmucks’ backs, every laser thingies looked like armless plastic artifacts.

And then… Bingo! I discovered the power of PLANTING AND PAYING OFF.

From that day on, using a knife, squashing an alien, or blowing a head felt great!

The concept is easily understandable and magical to use: If you’re going to use any dramatically charged tool or skill (a knife, an ability to throw things, a gun, a bomb, Aunt Liza apple pie), you need to plant it casually earlier in your story.

In other words...

If you’re going to kill the landlady with an axe, better present this axe way before splitting up the landlady’s head with it.

If Cathy Ames is going to shoot Adam Trask in the shoulder, it will work as a dramatic jackpot if you already clearly established that Cathy was a monster and a time bomb ready to explode.

Easy, isn’t it?

Planting and paying off: use it. And killing stuff will never feel so fine.

Sunday, January 16, 2011

Saturday, November 27, 2010

Trust this mysterious voice in your head

You’ve planed enough. You have a clear set-up, development and climax. You’ve sliced your project into sequences. Your plot and subplots are clear and cohesive. Your characters are motivated. Their objectives are comprehensible. Their goal set.

Fine! What to do next?

Well, forget about all you’ve planed and ignore all the rules!

When it’s time to write and struggle against the white pages, no advise, no expert, no script doctor or MFA can help you - all you need is to fine tune into this voice in your head.

Just like Joan of Arc right before she charged the Brits!

Louis Ferdinand Celine called it his little music…And writing is the ability to tune into your inner music.

If you can’t tune into this voice of yours – your very own style -, if you don’t feel that voice within you, and don’t get excited and moved into action by it, writing a full manuscript is going to be very difficult - by my experience, impossible.

We all have stories to tell. Great stories, really. Packed with actions and emotions. Twists and turns. But that doesn’t matter - because stories, and writing in general is not about what we have to say or report. It is NOT about how dramatic the situation or how original the set up.

It’s all about how we say it. How we hear it. When we follow and trust that voice in our head.

So fine tune into your mental music… and dance…

Thursday, November 25, 2010

Oh baby we really need to talk about Love

Don’t worry. I’m not about to get on my knees and babble about the inevitability of us.

This post is not about being in love (though I wish it was), this post is about the need of a strong romantic subplot in any given story.

You can’t escape it. Even if your story is an action packed intergalactic slasher affair, they will be an element of love. The main question here is not if you need a romantic subplot in your story – because you do – the real problem is to build and intertwine it with your main storyline so they flow harmoniously and naturally together.

The best way to do that is by connecting the main events in your storyline with the main event in your romantic subplots.

Let me explain:

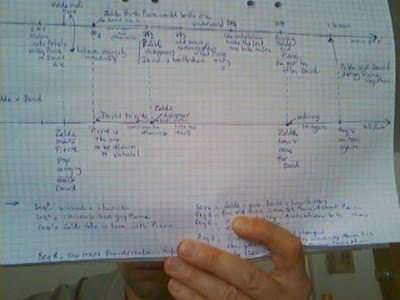

When you map your project, you can build a timeline connecting all the major events that form your story.

If you’re writing a survival story, all the major events on your main timeline will be related to surviving a given ordeal. If you’re writing a crime story, they will be related to finding who committed the crime, etc.

Beside the main timeline, you can build a set of secondary timelines, where you list chronologically all the major events that form the romantic subplots of your story.

For example, if you’re writing a story where all the major events relate to surviving a giant ape and escaping Skull Island

You’ll find yourself with series of timelines that would look something like this (that’s my own timelines and subplots for How I Stole Johnny Depp’s Alien Girlfriend, by the way - and there's my chin and fingers too ;) :

The trick is to connect all the major events in the main storyline with all the essential turning points in the romantic subplots.

For example, Kong kidnapping Ann Darrow is definitely a major event in the main theme of surviving and escaping Skull Island

If the major events in your main storyline are disconnected from the romantic subplots, there are big chances that the love story within your main story will feel artificial, unbalanced and somehow unmotivated.

Your work as a writer is to connect the dots between the different timelines and make sure that every major event in your main storyline says something about your romantic subplots.

If you do so, you can successfully convince people that a girl can fall for a monkey.

Wednesday, November 17, 2010

Further slicing: sequencing your story

When you’re writing, there are tools and tricks that will help you sail through this vast chaotic ocean that’s a first draft.

Slicing your story into comprehensible and clear segments known as "sequences" is one of the important tricks I learned as a student of the late Frank Daniel.

Frank Daniel thought that any story could be divided in smaller units that carried their own coherent dramatic spine.

Sequences are like the building blocks of your story. I like to think of them as "mini-stories" with their own conflict and resolution.

Each sequence's resolution creates the situation which sets up the next sequence, moving the story forward. Basically, it means that when you start working on your story, instead of sailing off into an endless ocean of situations and words, you step out into a carefully mapped collection of short stories.

Each short story will be a single coherent step in the full journey of your character.

Personally, I like to divide all my projects into 8 “mini-stories” of about 5 to 10,000 words each (an arbitrary habit I developed while working as a scriptwriter - but the number of sequences needed to tell a story really depends of the particularity of any given project.)

All my “mini stories” play an essential part in my manuscript, but I write them as if they stood alone.

What’s the point in that?

It allows me to ignore the fact that I’m sitting down to write a daunting 80,000 + words novel.

So…

Divide your work into smaller pieces. Drive your character from one resolution to the next. And you will be right as rain.

Saturday, November 13, 2010

You want to help your character: become his worst enemy

You love your character so much, you’re ready to spend the next six month of your precious life telling his/her story.

But your job is not to help and protect.

YOUR JOB AS A WRITER IS to hurt your HERO/HEROINE as hard as you POSSIBLY can.

There are two factors to assess the worth of a fictional character: (1) the amount of troubles he’s in and, (2) the amount of energy he employs to solve them.

The more troubles, the more fascinating your story.

If your character’s problems are small or artificial, his actions will be proportionally small and artificial. You will end up with a weak story.

You should never help your character. Never lead him to a crucial clue. Never save him from a grave danger – your job is to hide the clue deeper and create even greater dangers. Then, you let your character solve his problems all by himself.

Actually, each time you fix a problem for your character, you’re closing the door for more storytelling and development. Instead, when you’re adding yet another set of insurmountable obstacles, you’re pushing the story forward and giving your character more opportunities to prove his worth and captivate our interest.

If your character wants to be the world fastest running athlete, cut is legs

If he needs to save the world, make him weak and cowardly

If he loves the girl, kill the girl

YOUR JOB IS TO CREATE UNSOLVABLE PROBLEMS, YOUR CHARACTER MISSION

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)